Kings Highway

Kings Highway was another original stop on both the Brighton line and the Manhattan Beach Rail Road (MBRR). Although there wasn’t much to see around this area in the photos below, the major destination for riders using the stop would have been the Brooklyn Jockey Club. This racetrack extended along Ocean Parkway, eight blocks to the west of the station, from Kings Highway south to Avenue U (see map below). Its western boundary was Gravesend Avenue (renamed McDonald Avenue in 1933 to honor John McDonald, a 40-year veteran of the Brooklyn Surrogate Court who was killed by a chicken bone, according to this cheeky piece that paid tribute to his righteous son, Miles.). Since the Culver line ran along Gravesend, most gamblers would have opted for that surface train, if they had a choice.

Moving on, let’s get to the photos.

Above is another photo I found somewhere online, this one purporting to be “Kings Highway 1888.” Er…nope. The date has to be post-1899 because of the trolley wires and poles. Film seemed to be at a premium over a century ago, so most rail photos fell into the “We-Need-to-Document-This-Change” bucket. In this case, it would be the electrification of the Brighton line by the Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT) company, which places it squarely in 1900 and prior to the 1906 onset of the grade crossing elimination. (BTW, a large part of the line was electrified in 1899, then BRT reverted to locomotives for a bit, but all of the Brighton tracks remained juiced from January 1900 onward.) Electricity, of course, rules out the MBRR, which was never electrified. Just hope it’s the Brighton (not the Culver) line!

It does seem clear the photo is looking toward the Kings Highway grade crossing, just above the shelter on the left and a small flagman’s cabin across from the shelter on the right…Looking further at the fur trees on the right and the line of smaller trees on the left, and comparing them to the 1906 photo below, Houston, I believe we have a flora match for this vicinity. Yup, this is the Brighton stop…I hope.

Above: Looking west past the grade crossing in the foreground down Kings Highway. By the way, photos bearing a reference number on the bottom left with a “B” prefix, and a date on the bottom right, are BRT photos. Many photos over the years had such labels cropped out.

The Brighton roadbed would need to be elevated onto an earthen embankment beyond Avenue H starting in the Spring of 1906. While that was happening, the Brighton trains would need to operate on the MBRR tracks, using steam-driven locomotives. City-bound passengers would change at Fiske Terrace for the electric cars. This inconvenience would last well into 1907, but given the meager population south of Fiske Terrace, there weren’t many furious letters to the editor. However, residential developments to the east, north and south of the Brighton Kings Highway station would create many new riders: Slocum Park, Homecrest, King’s Oaks and Kingsboro. Hmmm…Kingsboro…Well, therein lies a tale.

The Wood, Harmon Company initially dubbed the 2,300 empty farmland lots they started hawking in May 1902 – south of Kings Highway to Avenue T and west of Ocean Avenue to the tracks – as “Brooklyn’s Harlem.” Indeed, a title search for homes in this area will find a reference to the original survey map filed with the City on May 23, 1902, labeled “Brooklyn’s Harlem.” Why Harlem? Daily press ads by Harmon breathlessly explained: “Because of its strategic business and residential location.” In other words, the area’s many transportation options made it strategic: Ocean Avenue trolleys, the Brighton train to the Fulton Street EL that took riders over the Brooklyn Bridge, and the MBRR which would “soon” (in reality, never) whisk Brooklyn Harlemites through the LIRR’s planned East River tunnel to Penn Station.

But Brooklyn’s Harlem needed a new name, or so their ads shouted. Name it and win a cool grand!

The Company received over 10,000 suggestions, some of the losers being: PingPongVille, U-Need-A-Home-Site, Bully-Land (inspired by Teddy Roosevelt), Just Rite, The Midway, Resident’s Grassy Paradise of Ocean Avenue, The Ideal Pioneer Enterprise Park, Brooklyn Continued, and in a name that only David Bowie would have favored, Young Americans City. The winner was to be announced over the Labor Day weekend. But alas ad alack, the Wood, Harmon controller was stuck aboard a storm-tossed trans-Atlantic steamer and the award had to be delayed…and delayed…Until finally, Wood, Harmon having sold 95% of their lots, decided to bite the bullet and make a spectacle of it all.

On October 4, 1902, despite heavy rain, hundreds gathered in a field at the corner of Avenue Q & Ocean Avenue. Q was renamed Quentin Road 20 years later, of course, to honor Teddy Roosevelt’s son, a flying ace shot down over France in 1918. Thank God or we’d probably have QAnon nuts gathering there today.

Anyway, Wood, Harmon was looking for a name that would take up less ad copy than all those wordy proposals, so they chose Kingsboro. There were 27 winners and rather than get a grand each, they shared the prize and everybody supposedly got a check for $37. Yeah, right.

This promotion was so successful that Wood, Harmon used it again a few years later to rename Midwood Manor per Part 3 of this saga, but alas, “Parkway Gardens” (the most popular submission) and 200 other names were all deemed inferior to Midwood Manor. Yeah, right. In any event, all of the names Wood, Harmon used for the areas where they sold land eventually fell out of use.

Above: Kings Highway, looking west from the recently abandoned MBRR grade crossing along East 17th Street. The new trestles in the distance now carry the MBRR and Brighton trains. The old tracks and warning signs on E. 17th have yet to be removed on the bottom left. A Brighton train is visible in the middle far right of the frame and the roof over the station platform can be seen in the distant middle left. While the steel viaduct had been installed in 1908, it wasn’t until January 1909, the date of this photo, that the station was finished.

Above: Looking north to Kings Highway along the embankment on East 16th. The MBRR trestle is on the left and an old house belonging to the Ditmas family is on the right. It would soon be dragged a few blocks away. The embankment on the far corner is the site that the Dubrow family bought when the MBRR trestle and right-of-way were demolished in 1939 as explained below.

Above: Looking west from East 17th Street at Kings Highway to an MBRR locomotive on the trestle (left center).

Above: Camera positioned outside the Kings Highway station looking west along the Highway.

Above: Kings Highway, looking southeast to the Brighton platform above. As to why Kings Highway became an express stop, the 1900-1909 photos above provide a pretty good reason: there was plenty of room to expand!

Compare Photo of Kings Highway & E 16th St Above (Looking Southeast) with 1961 Below:

Dubrow’s Cafeteria,1939:

Avenue U

Above, I marked the Brighton stations in red and the MBRR stations in green. The Sheepshead Bay spur off the MBRR is in yellow. The Brighton spur is not shown. Note the empty land between Kings Highway and Avenue T – the new “Kingsboro.”

The map shows that Avenue U sat within the Homecrest development. But east of Ocean Avenue there were only farms and marshes. A local stop since it was opened, sometime around 1900, only the Brighton trains stopped at Avenue U.

Sign on the station, far right above, reads: “Trains stop on signal from platform.”

Per news story on right, I speculated in Part 3 that the BRT favored Avenue K over Avenue J because a huge new athletic field was on the horizon at Avenue K. But why would they favor T over U? Did “Avenue T” sound better than “Aven-You U”? Maybe. But the shift would have placed the station equidistant from Kings Highway and Neck Road, so that may be the explanation. Or maybe not! $1,000 for the winning answer! Email Wood-Harmon@fake-contests.com!

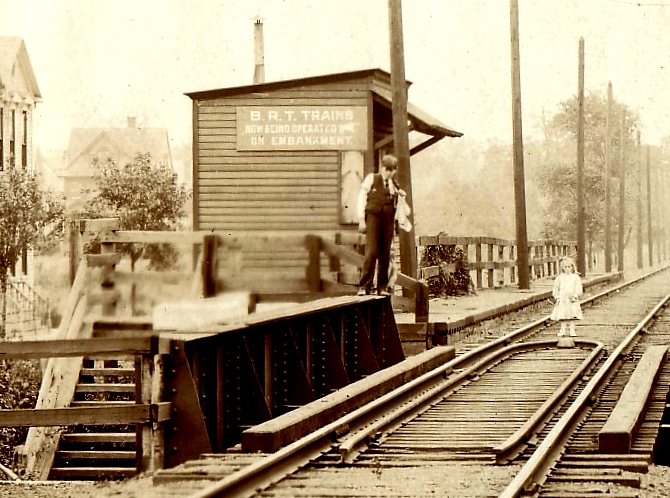

“BRT trains now being operated on [this new] embankment” reads the sign. For more, see Arthur John Huneke.

Below Right: Avenue U – trestle visible in center distance – presumably looking west from Ocean Avenue.

Above: Avenue S looking west from East 17th Street showing Brighton cars. The view along Avenues R & T would have looked the same.

In 2005, the Avenue U station was added to the National Register of Historic Places, but in 2008 it was demolished and replaced. The Subway Gods giveth and taketh away.

Neck Road

Neck Road was another original stop for both railroads. Why? The Coney Island Jockey Club, formed by August Belmont, more commonly known as the Sheepshead Bay Racetrack, opened just to the east in 1880. Both lines built short-distance spurs to bring passengers closer.

Above: Sheepshead Bay Racetrack Station looking north on MBRR tracks. BRT trolleys are on the far left. In 1908, most gambling was outlawed. In 1910, ALL gambling was abolished at racetracks and they soon folded. The spurs were abandoned by 1916.

Above: Coney Island Jockey Club aka Sheepshead Bay Racetrack, east of Ocean Ave. Neck Road is at the extreme top left. Terminals for the trains were just west of Ocean Avenue, between Avenues X & Y near the entrance that led to the grandstand.

Above is a 1910 LIRR Blueprint with Arthur John Huneke’s annotations. The top of the map shows the entrance to the racetrack at Ocean Avenue. The bottom shows the trestles carrying the “B.R.T.” aka Brighton (bottom/west) and the MBRR immediately east of it. The BRT spur ran under the trestle between Avenue X and Avenue Y.

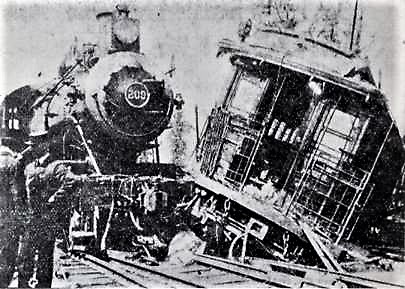

In the photo left, the Brighton trolley is on the right and the MBRR locomotive is on the left at the grade crossing near the Sheepshead Bay Racetrack. Oops.

The flagman who should have prevented this collision was nowhere to be found after the incident according to the news story (left). Back in the early years of the 20th century, police routinely arrested train and trolley operators after EVERY crash or passenger injury until their culpability or lack of it could be sorted out.

Finally, in 1908 a new 8-inch water main had to be installed from Neck Road to Brighton Beach to take the place of an old main covered by the new earth embankment. The cost? $7,000 which would be $222,400 in today’s coinage. Not bad.

As for the racetrack, it continued to serve as a venue for the Police Department’s charity games, drawing up to 70,000 paying onlookers every year. And the renowned tenor, Enrico Caruso, sang there during World War I to raise money for Allied troops. But by 1923, developers won out.

The property had been auctioned off in lots months before the photo above – the streets have been laid out but home construction has been piecemeal. The realtors dubbed the area “New Flatbush,” which lasted about five minutes.

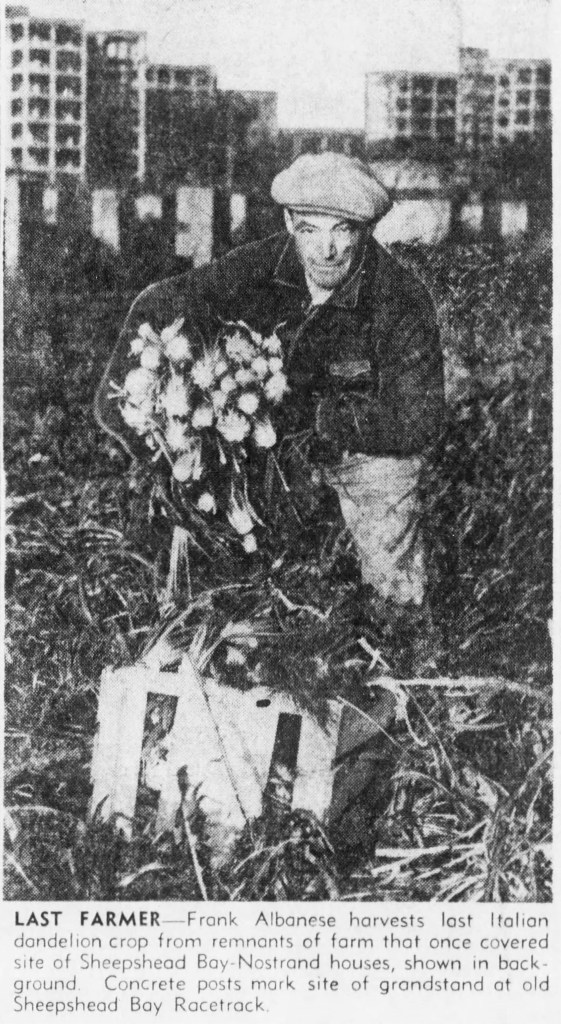

After WW II, a large chunk of the area became the Sheepshead-Nostrand Houses in 1949-1950, displacing the last remaining small farm in the area:

But let’s end the Neck Road segment with the trains and the MBRR staircase to nowhere, still surviving almost 100 years after the 1924 abandonment of passenger service. Photos date from 1986 to 2022.

Sheepshead Bay

This fishing village was another original stop for both lines. But the new station would be a tight squeeze.

Beyond Sheepshead Bay

After Grade Crossing Eliminations

Above: Photo of Manhattan Beach looking east from Brighton Beach. In the exact center, above the empty field, is the MBRR station. That is now Corbin Place, a 4,000-foot long street, originally named in recognition of the robber baron, Austin Corbin, a notorious anti-Semite who developed and named Manhattan Beach and the railroad that brought people there to his hotels, starting in 1877.

It was renamed for Margaret Corbin in 2007, a more enlightened Earthling. But it’s still Corbin Place, because first names don’t make the cut on NYC street signs. I’m not making this up.

FREIGHT REPLACES SUN-BATHERS

After the grade crossings were eliminated, passenger operations on the Manhattan Beach Railroad’s steam-driven locomotives continued to decline. Passenger service on the Bay Ridge line west of the Manhattan Beach Junction had stopped even before the tracks were depressed and now the third-rail alternative offered by the BRT was cheaper, faster and exponentially more frequent. By 1920, when the new tunnel was built for the Brighton line under Flatbush Avenue, connecting Prospect Park to new stations at 7th, Atlantic and DeKalb Avenues, and thence to downtown Manhattan, the MBRR was only running a few trains a day for commuters from Manhattan Beach to Long Island City and thence to Manhattan. A round-trip on the MBRR was 40 cents versus 10 cents on the Brighton. Need I say more? Service ended in 1924. Freight became the focus of the Pennsylvania Railroad conglomerate as it eyed its new railbeds. Spurs sprang up along the Bay Ridge line serving more commercial customers, and an existing spur on the MBRR at Avenue N to Avenue O began to take coal deliveries.

The insurance map above shows lumber yards east of Coney Island Avenue & south of Avenue H, which were serviced by a spur of the Bay Ridge Line. There were many more spurs like this.

Above: This is where the LIRR freight yard was located, between Avenue N & O. On the far upper left are the MBRR tracks on the embankment looking south.

But as the empty spaces along the tracks began to fill up with new houses and apartments, citizens railed against the noisy LIRR behemoths. As a result, in 1927 the railroad was forced to electrify the line with catenary wire strung from poles. Just like trolleys – but with a hell of a lot more juice flowing through the wires.

As time rolled on, even freight traffic declined because many customers switched to trucks.

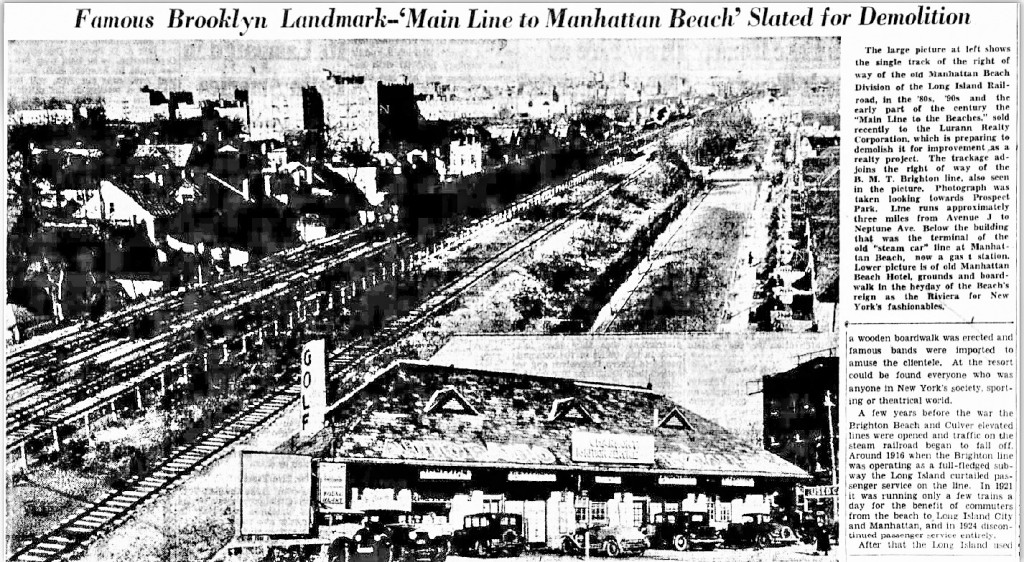

After passenger service ended in 1924, the LIRR used its two MBRR tracks for limited freight traffic. But by 1936 business was so light, only one track was needed, as pictured to the right of the four Brighton tracks above. And in 1937, even freight operations ceased. The insert in the bottom of the photo above shows a gas station that had served as the MBRR terminal station on Corbin Place, as previously discussed under the 1900 photo above.

In late January 1939, the Lurann Realty Company, which had purchased the entire 45-foot wide MBRR right-of-way from the LIRR, began removing the earthen embankment, 300 tons of rails, and 1,500 tons of steel trestles. Miraculously, no Brighton trains flew onto East 16th Street as a result. And surprisingly, I could find no photos of the Lurann demolitions.

The Bay Ridge line was electrified via catenary wires in 1927 but that was discontinued in 1967 in favor of diesel-powered locomotives. Today, only a couple of freight trains a day traverse the line to and from rail float barges at the foot of 65th Street in Bay Ridge.

The MTA is now conducting a study to determine the feasibility of building a light rail passenger system, “The Interborough,” alongside this freight line, which would link up with most of the mass transit lines in Brooklyn on its way to Jackson Heights in Queens.

In a recent “town hall meeting” (September 22, 2022), the MTA announced its engineers were leaning toward a light rail option.

ADDENDUM: Odds & Ends

1918 LIRR Maps Showing the Grade Crossing Work:

My Favorite Things: Recommended Reading

AUTHOR’s NOTE

I grew up a few blocks from the abandoned Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) station below the junction of Flatbush & Nostrand Avenues. My pals and I would often explore that area, especially a rotting wooden platform, taking care not to disturb a Hobo colony on its periphery. Life would take me elsewhere until my 40th year, when I somehow found myself living near that abandoned site again, in a small neighborhood with nine cul-de-sacs created by the Brighton and LIRR train lines that intersected just below Avenue H, the southern boundary of Victorian Flatbush. Curious to learn about the history of these parts, I began exploring books, maps, old newspapers, and Internet sites, collecting many images over the decades. These posts represent what I learned. My aim here was to present a broad history of two rail lines, integrated with the development of the land they traversed. Realizing that many readers probably have more substantial knowledge, I encourage suggestions for correcting any factual errors by commenting below.

I’ve seen many of these photographs previously, but thanks for the great work in stitching them all together with comparative photos over the decades and with your commentary!

LikeLike

From 1939 to 1952 my family lived next to the Brighton line across the street from the Newkirk plaza. Was able to look down at the trains going and wave to the passengers on the trains. I left to join the navy in January 1952 and mom and dad moved to Avenue H and again next to the subway station on the 15th street side before you went under the tunnel to the station over the candy store. Mom and dad ended up on Rugby rd and Foster Avenue later on in their lives. Dad hung out on the Newkirk plaza for many years

LikeLike

A fascinating read. Thanks.

I grew up on Avenue I near Utica Ave.

LikeLike

I currently live in one of the homes built over the Sheepshead Bay racetrack on E. 22nd Street ( nee Elmore Place), off Avenue U. Over 30 years ago I went to an exhibition at the Brooklyn Historical Society, where a photo of my block was displayed, showing the houses going up, ( at some point between 1920-25) and also of the construction of PS 206 down the block, which I can only assume was to accommodate the children who would be living in all the new surrounding developments. I have never been able to locate those photos since, especially the ones showing the homes. Would you have any better luck?

LikeLike