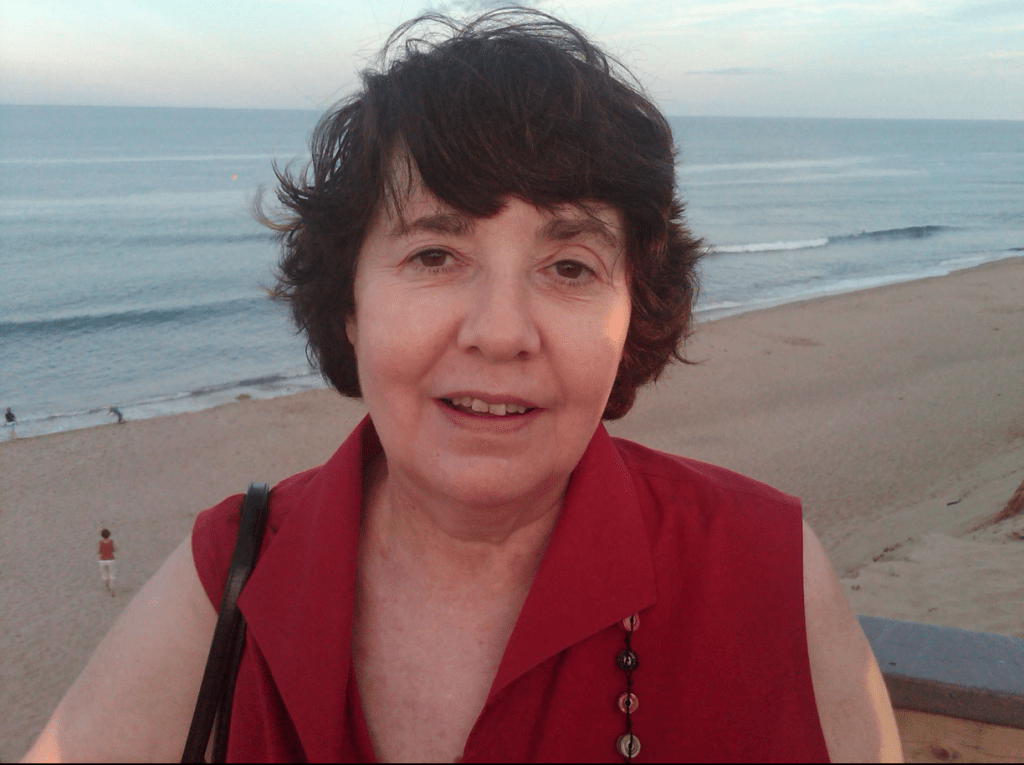

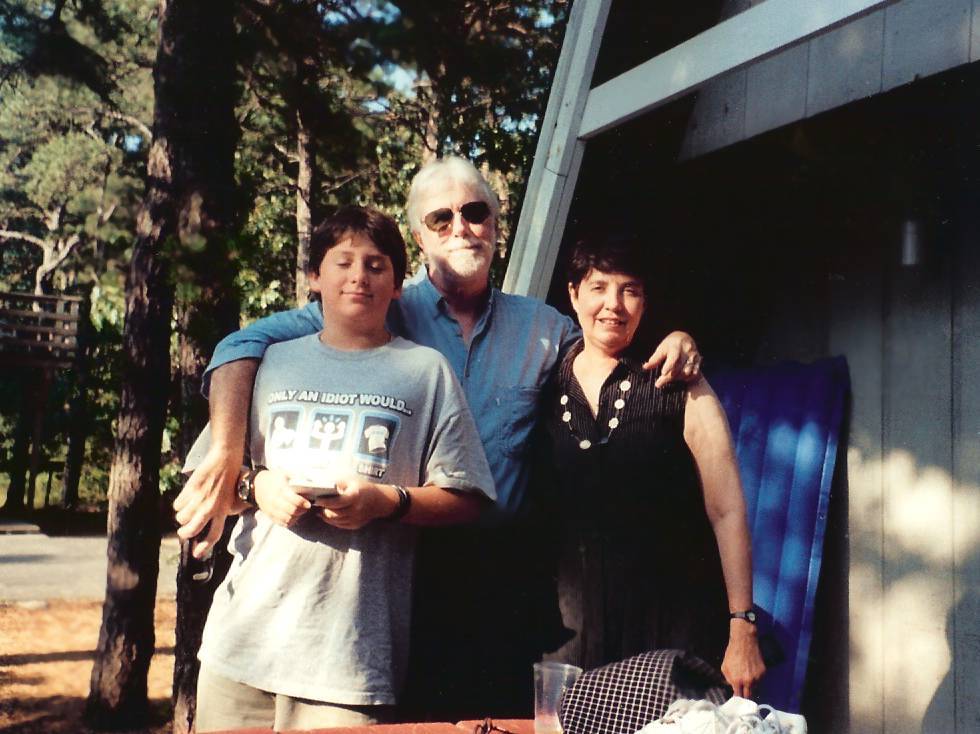

When your partner dies, it takes a while to adjust. So many special days come and go with only memories to hold. Like our wedding anniversary and the day we met, always celebrated at a fancy restaurant, just like that first night, getting off the IRT New Lots train when I talked her into dinner at Camperdown Elm on Union Street. And so many beaches where Virginia loved to lie: March in Fort Lauderdale, Sumer in the Rockaways, late August on the upper Cape. But October was the true “missing you” gauntlet: our son James got married on Columbus Day weekend in the Catskills – her birthday. The first without her. We used to take car trips up there to enjoy the Autumn leaves.

Then the Flatbush Halloween Parade that Virginia had managed for decades was upon us. And yet, it all went well. Very well.

Until November. The sudden onset of late afternoon twilight and cold nights provided the perfect meteorological accompaniment for the grief that flared anew upon finding in my winter coat a list of the few TV channels that had good reception in her hospice room…

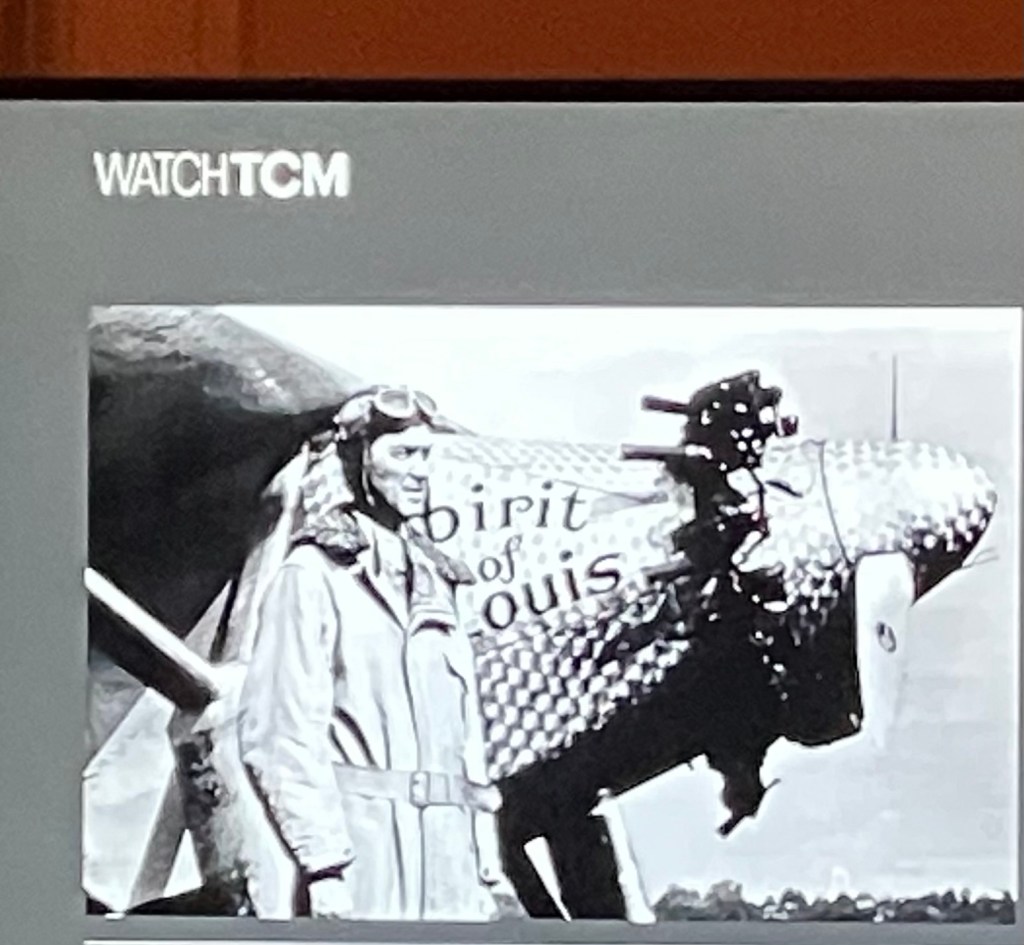

The last time we talked we were watching Jimmy Stewart in Spirit of Saint Louis on TCM. She hated all-male movies but she was so worn-down, she didn’t complain. She had double-vision since the cancer spread to her brain two weeks earlier but her hearing was still intact and Stewart’s voice was so likeable, she appreciated that he narrated what was happening on his famous flight for most of the movie. But the pain started to creep up and she asked me to press the morphine pump that I got the Doc to install. My last gift for her – it blotted out the pain, and gradually her speech, and she slipped away.

After the wake and memorial service, I would hear Bogart’s Sam Spade whispering to me, “When a man’s partner is killed, he’s supposed to do something about it.” But she wasn’t killed, there was nobody to blame, and there was nothing I could do about it. Until a friend sent me the Death Cab for Cutie cut, “I’ll Follow You Into the Dark.” It got me to thinking magical thoughts. And so, despite considering myself an above-average American when it comes to being sensible, I scheduled a reading with a medium.

Many song writers have written about encounters with mediums/psychics/fortune-tellers, calling them gypsies. In 1962 Lou Christie’s gypsy became so despondent about his future prospects that she started sobbing. Yikes. On the other hand Bob Dylan’s Spanish Harlem gypsy saved him back in 1964. Truth is, I just wanted to find out how my wife was doing eight months after passing over the Great Divide and I ain’t talkin’ about the Rockies.

So I did some research and found me a psychic certified as cosmic by some such society for the vetting of supernatural seers. Plus, she was retired from the military and liked classic rock, characteristics not often associated with mediums, which was fine with me. After creating a new payment method to shield my identity, I scheduled a Zoom.

The protocol was simple, she said. No chit-chat. Just hello, let’s get started, and “just answer yes or no if I ask you a question.” She meditated very briefly and then…She was immediately contacted by someone who wanted to sit next to me and run her fingers through my hair because she loved me. Well, that was worth the hundred and fifty bucks right there! But the medium persisted:

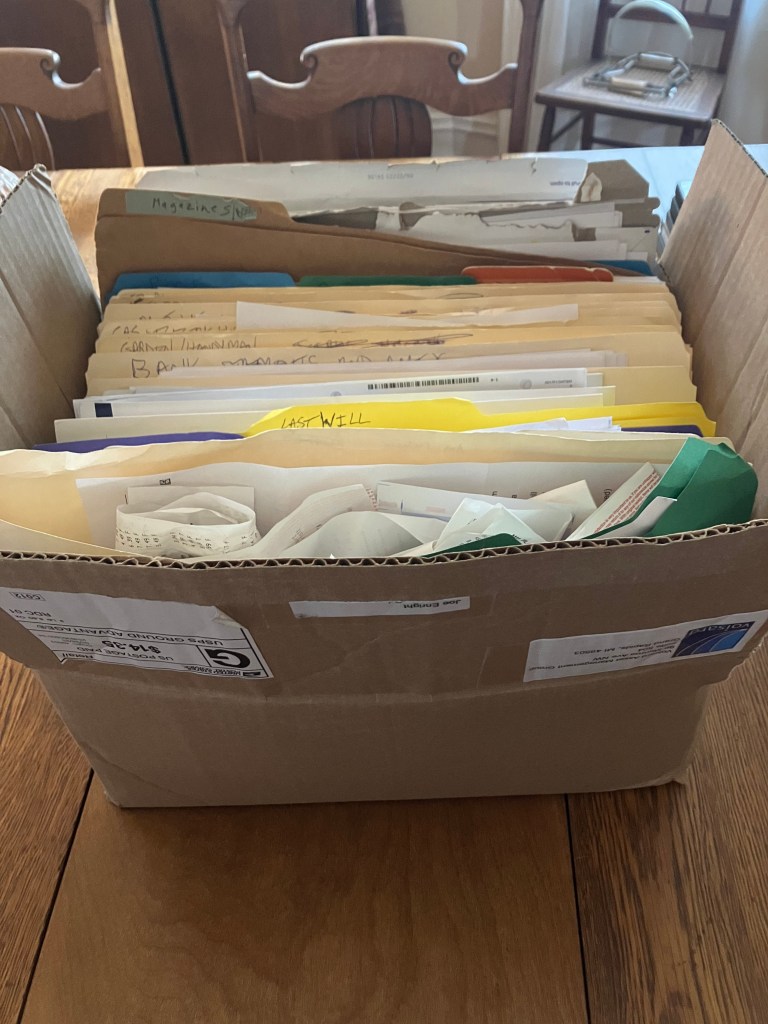

She had suffered from many ailments all over her body and used a lightning-bolt image to describe the back pain that afflicted her. It was all too sudden, her passing, no time to prepare. She was concerned about my blood pressure and wanted me to eat more, to take care of myself. She was glad I was playing guitar again and working with Linda. She had always looked out for me, making appointments and handling the finances and the calendar, reminding me of things. She then showed the medium an image of a cardboard box that was very important and saw me with it. She was proud of me, of what I’d accomplished. Finally, the medium described the spirit as having a keen sense of presentation and display, and a very clever sense of humor. She didn’t share her feelings of need, because she was more interested in trying to help others. I teared up hearing that because it was a perfectly succinct assessment of the woman I lived with for 40 years.

Most of the details were accurate:

-Virginia suffered from a broken back that impelled her to recline for half of her waking hours.

-From the cancer diagnosis to death took one month, most of it in pain.

-I recently experienced a blood pressure spike for the first time in my life.

-I’ve lost 10 pounds since she died, missing a lot of meals.

-I started playing guitar again after many years away from it.

-I had been working with Linda, a friend of Virginia’s, on the Halloween Parade.

Most astonishing was the cardboard box. After she died, I removed all our important paperwork from Virginia’s desk and kept it in folders. But they were hard to access quickly, strewn about the dining room table. So I found a cardboard box that was just the right size. I began notifying pensions and banks, canceling credit cards and flights, tracking expenses in a spreadsheet, filing for probate, managing claims for eight separate funds/investments, etc. During all that, I discovered her broker/advisor had lost his license which explained his failure to render any assistance. That made me work even more feverishly to transfer all the funds to a mainstream investment company, as opposed to the backwater entity he had selected. All of which I documented in that cardboard box.

The medium thought it extraordinary that the spirit was able to see me taking my blood pressure, playing guitar and working on financial matters with the new box. I sheepishly admitted that I still talked to Virginia when I was home alone so maybe I bragged about my cardboard box. She smiled and the half hour was up.

I’ve always preferred to think there is an afterlife for deserving souls. Maybe because I saw a ghost when I was a kid. But more importantly, I liked Pascal’s Wager: if I was wrong about a hereafter, I’d never know, but thinking it might happen would certainly give me some comfort in confronting death. I talked about it often with Virginia after we knew she had only two weeks to live. As she faded, she seemed more receptive to the idea when I told her perhaps her beloved grandmother and her friend Susan who passed during the pandemic would be there to greet her, and especially her first love, Dewey, who died way too young. I also assured her that if there ever was a deserving soul, she fit the bill. Plus she’d finally collect that battle pay for putting up with me for 40 years.

In the end, it’s all beyond me. But in the days that followed, I played my Martin a lot and after an occasional shot of Dewars, worked up a melody for a song based on what I’d whisper in her ear while I stroked her hair that last sad night as Jamie and I kept vigil. I figured if there was a hereafter, maybe new souls get better treatment if they’re remembered and honored by those they left behind. And maybe singing songs about them counts extra. So I sang to her about the train that took her away from all the pain to a place where she could see clearly once more, ride a bike and roll in the waves, hoping we’ll all meet again some day on another train, not too far away. On another train, on a brighter day.

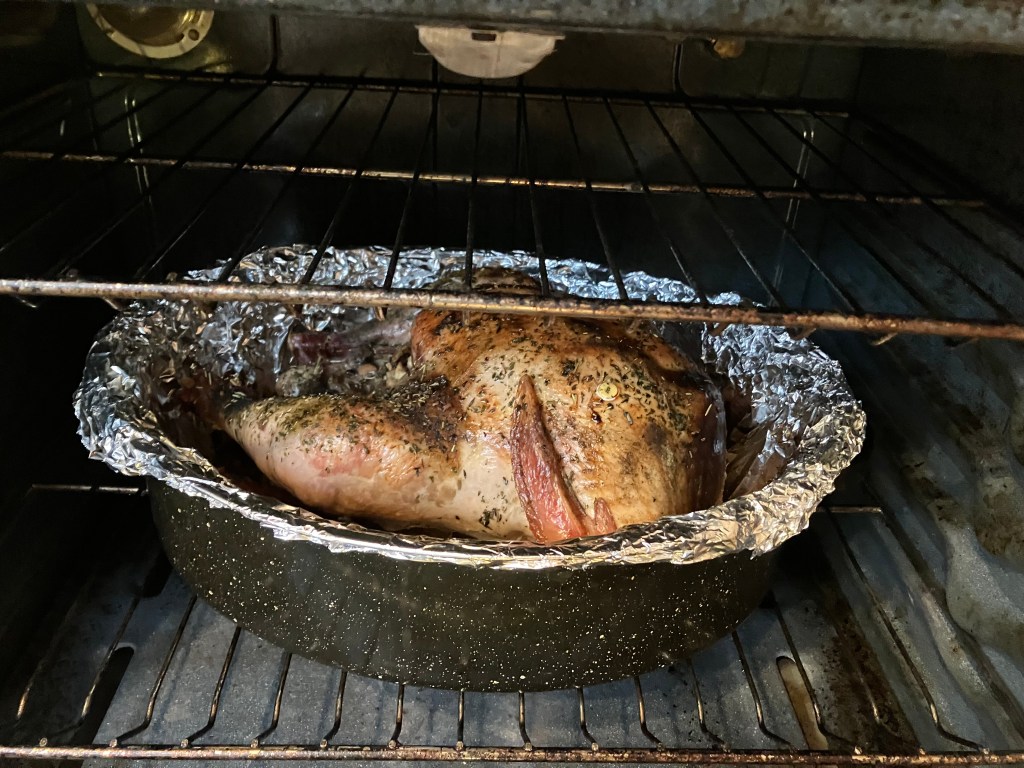

Now that we’re in December, I know the grief will ebb and flow, getting the house ready for the holidays, decorating the tree and the like. But as Jamie and I prepare her Christmas dinner recipes – a lineup with more moving parts than Beethoven’s 9th, I like to think she’ll be looking in on us now and again with some silent encouragement not to overcook the asparagus.

…Laugh and talk of me as if I were beside you there.

And when you hear a song or see something I loved,

Try not to let the thought of me be sad…

There are so many things I wanted still

To do—so many things to say to you…

Remember that I did not fear—

It was just leaving you that was so hard to face…

We can’t see Beyond…

But this I know:

I loved you so – it was heaven there with you

-Isla Paschal Richardson

Ian and I would often talk about the possibilities of life in other dimensions. We humans experience life in three dimensions, but mathematically we know more exist!

My father always said “ You don’t know, what you don’t know!”

I happen to be in Florida helping Ian, Annie and my precocious granddaughter Gavi relocate. After I read your message, I played the following song for her.

It’s Virginia and Joe dancing in one of those spaces, many others forbid us to luxuriate in!

LikeLike

Wonderful video, Steve. Agnes is angelic. Thank you!

LikeLike