My high school history teacher said something I never forgot: “Listen, you morons, and I’ll explain it again! Most of you have a relative who’s fifty years or older. When he or she was born, they probably had a relative who was also that old. Keep going back like that and it will take just 40 consecutive fifty-year-old ancestors before you wind up in the time of Julius Cesar and Jesus Christ. In fact, it would only take 600 consecutive ancestors to trace the entire history of man before we were apes. Why, they could all sit together in the balcony of the Loew’s Kings!”

Images of Celtic cave men clobbering Brooklyn longshoremen in my favorite childhood movie theater still haunt me to this day. Anyway, I grew up on Flatbush Avenue and the only thing reminding me of something older than the day I saw Godzilla, King of the Monsters at the afore-mentioned Loew’s Kings was the steel remnant of a trolley track – dating back only one ancestor – that peeked out here and there from the crumbling asphalt in front of my home.

But in less hardscrabble environs, such as the far eastern end of the very same loooong island on which I lived, the past can be better appreciated. There, history is a living thing, particularly in East Hampton which was the first English settlement in all of New York. For instance, every two weeks the East Hampton Town Trustees meet. This is not the Council that manages all the Town’s affairs. No, the Trustees merely oversee the harbors, bay beaches and freshwater ponds. But they’ve been doing that since 1686, when patents from the King of England told them to keep meeting lest they forfeit their oversight.

Today’s living embodiment of East Hampton’s institutionalized respect for history is its Town Crier, Hugh King, who can also trace his lineage back to Colonial times despite his birth in Bay Ridge (which might explain his affinity for National League baseball). Retiring after three decades as a Springs teacher in 1996, Hugh became caretaker of an historic Main Street home-turned-museum. And calling upon 35 years as an amateur thespian at a local theater, he would also dress in a Crier’s colonial garb to give walking tours on behalf of the Town. In 2018 King and his wife, the late Dr. Loretta Orion, an anthropologist, published a study of the 1657 witchcraft trial of an East Hampton midwife.

That trial would only be seven 50-something lifespans ago if you’re keeping score at home.

Hugh King was officially named the Town Historian in January 2020, the tenth resident to take that role since Governor Al Smith signed the “Historian’s Law” in 1919, requiring every “city, town or village” to have one. {See List Below} In an interview after his non-paying appointment, Hugh acknowledged the contributions of his predecessors. One of the names he mentioned was Morton Pennypacker.

Frank Knox Morton Pennypacker was the only Town Historian born off the Island. He emigrated from Philadelphia by way of Asbury Park, Kew Gardens, Mineola and finally, East Hampton. History seemed to run in his family’s blood: when he was four years old, a cousin named George Custer went toes up at the Battle of Little Big Horn and during his Asbury Park days running a printing business, cousin Samuel Pennypacker, a combatant at the Battle of Gettysburg, became the 23rd governor of Pennsylvania.

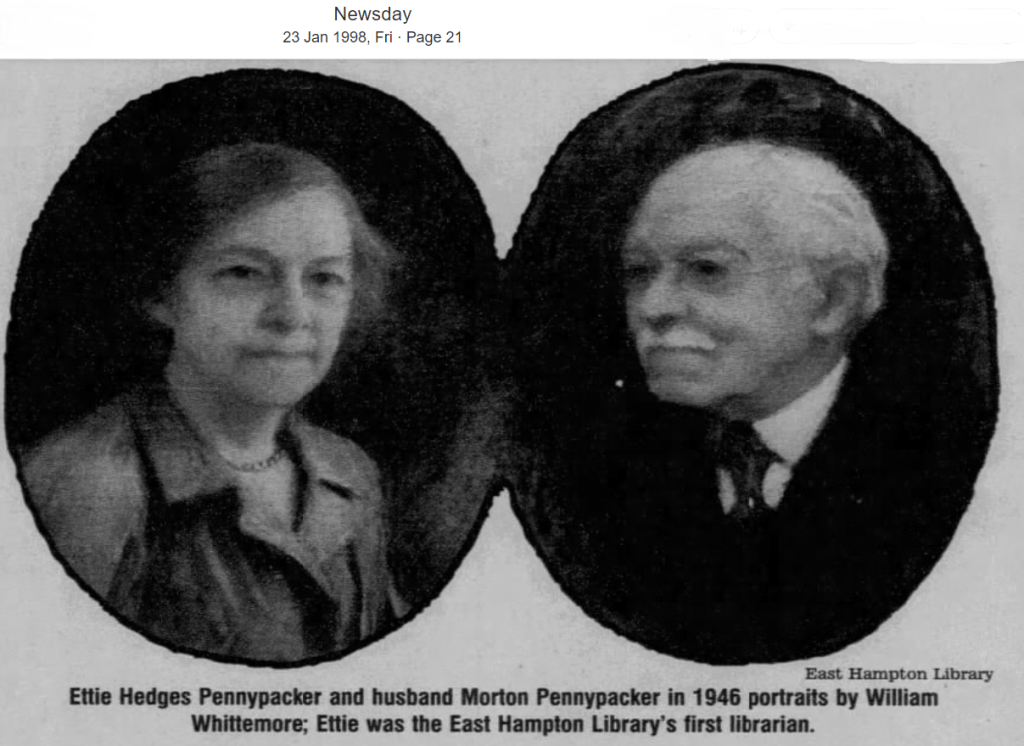

During his New York travels as a greeting card salesman, Pennypacker began collecting old books about Long Island, then expanded to old letters, maps, pictures and basically any artifact that would help inform its history. In 1928 he began contributing articles to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle about his Colonial era findings, filing almost sixty stories in the next two years. In 1930, he donated 2,600 books and thousands of pamphlets, manuscripts, clippings, and other items to the East Hampton Library, where the chief librarian since 1899 was Ettie Hedges, descended from 17th Century settlers. They would wed six years later and reside in Ettie’s venerable wood shingle house down the block from the library.

In 1935 East Hampton named Pennypacker its second Town Historian. Four years later he became famous for confirming the identity of a pivotal player in George Washington’s spy ring during the Revolution – Robert Townsend of Oyster Bay – thanks to his dogged pursuit and analysis of handwriting samples. And in 1943 he was appointed the official historian of Suffolk County. He stepped down from his posts only a year before his death in 1956.

Not quite one ancestor later, East Hampton citizens residing on Montauk Avenue – a very short path off Old Northwest Road – got tired of their mail and packages being misdirected to the much longer Montauk Avenue off Hands Creek Road. They petitioned the Town Clerk, Fred Yardley, to rename their little street and he obliged, dubbing it Pennypacker Drive to honor the memory of the little old man who helped him out whenever he visited the library as a kid. But when the new street post was pounded into the ground it read: “Penny Packer Dr.” Groan. The same residents complained about that new name, no matter if it was one word or two: it was just too weird. So the name was changed again in 1993, this time to one they chose: Country Lane. One has to wonder if their runner-up choice was “Generic Lane.”

But the preservation instinct still lives on in East Hampton. Take the November 4th annual Landmarks Luncheon of The Ladies’ Village Improvement Society (not to be confused with the Kinks 1968 hit, The Village Preservation Society, with its chorus of “Preserving the old ways from being abused / Protecting the new ways, for me and for you / What more can we do?”). Their focus now is on protecting homes built in the twenty-year period immediately following World War II: “Small, often whimsical beach-house pavilions with flat roofs and floor-to-ceiling glass…the most architecturally significant architectural idiom of our region.”

As the eighth Town Historian, Stuart Vorpahl, might have said in his old Bonacker patois, harking back to Kent and Dorset seafarers: “History never gets old, yes, yes, bub.”

The Ten Town Historians of East Hampton

J. Calvin Hadder (1920-1934) Owned a poultry farm with 250 hens as of 1921. A World War vet, he compiled a book about East Hampton’s role in the Great War.

Morton Pennypacker (1935-1956) Wrote The Two Spies, Nathan Hale and Robert Townsend (1930) and General Washington’s Spies on Long Island and New York (1939).

Kenneth Hedges (1956-1957) Nephew of Ettie Hedges Pennypacker. Had been Town Assessor, making him intimately familiar with the area’s houses and lands.

Richard T. Gilmartin (1957-1959) A Town Clerk for 20 years prior to appointment, he surrendered the post when elected Town Supervisor.

Richard A. Corwin (1959-1969) Former treasurer of the Town Historical Society which owns and oversees the Clinton Academy Museum and the Mulford House & Homestead. An expert at restoring antique furniture, in 1961 he reported receiving a letter at his Springs Road home with a return address of Race Lane, not far away. It was postmarked in 1930.

Carleton Kelsey (1973-1985) Teacher, furniture restorer and Amagansett librarian for 35 years. Born in an old Devon Road house where he said, “When the winter wind blew, the rug would lift right off the floor.” In 1997 he published Amagansett: A Pictorial History 1680-1940. An amateur actor in his youth, he was very good at imitating the Bonacker speech patterns of Baymen like Stuart Vorpahl which dated back hundreds of years. Following the scattering of his ashes in 2005, friends toasted to his life at the Amagansett library he loved so much.

Nettie Sherrill Foster (1990s-2007) An East Hampton native born on the Sherrill family farm, purchased in 1792, she was Town Co-historian with Stuart Vorpahl until her death. As a WWII WAC, she met and married an Army Air Force officer and moved to Dunkirk along Lake Erie. Returning home following her divorce, she was named director of the East Hampton Historical Society in 1979. “Sherry” was an expert in the development of “resort architecture” in East Hampton during the post-Civil War era.

Stuart Vorpahl (2009-2016) A US Navy vet (naturally). In 1963 a neighboring potato farmer handed him a typewritten copy of a 1686 document, saying “These are your rights. Defend them all.” A life-long fisherman, he carried a laminated copy of that document, known as the Dongan Patent, issued by King James II to his New York governor, Thomas Dongan. It described the rights of six English towns then established on Long Island to “enjoy without hindrance” the “fishing, hawking, hunting and fowling” within its borders forever, subject only to the administration of “one corporate body to be called by the name of trustees.” Which explains why East Hampton has been electing a Board of Trustees ever since. Vorpahl himself was elected to the Board for ten years. Four times he fought State arrests for fishing without a license, waving the Patent in his defense. Notwithstanding counter-arguments – that acknowledging the primacy of the Patent would also require East Hampton to pay a substantial annual tax to the ruling monarch of England – Vorpahl retired undefeated. Eulogized as “a fierce defender of the rights and traditions of the common people [who] could spin a tale and recite history at will with a good sense of humor while making his point,” Vorpahl generated nineteen New York Times stories about his Patent, his Bonacker culture, and various Town disputes. Always good copy, the Times nevertheless failed to publish his obituary. His ashes were burned on a floating miniature Viking vessel off his beloved South Fork in 2016.

Averill Geus (2009-2019) Named co-historian in January 2009 with Vorpahl, she had an ancestry just as long. Together with Hugh King, she rescued the head of John Howard Payne from Randall’s Island after the statue on which it rested had been vandalized in Prospect Park.

Hugh King (2020-Present) Amagansett resident who has delighted generations of East Enders with his humor, broad knowledge and humility. In October the 1804 Pantigo windmill was renamed in his honor, located behind the Home Sweet Museum, commemorating the birthplace of Mr. Payne who penned the 1823 chart-topper, Home Sweet Home – be it ever so humble and such.