Just north of Defonte’s Columbia Street sandwich mecca there stands a three story brick apartment house, 12 Luquer Street, built in 1885. There one can find a surviving example of how contractors once advertised their work. Instead of an ugly temporary placard stuck in the front yard, this company embedded a very small iron plaque in the front wall at eye level: M. GIBBONS & SON, BUILDERS, 318 COLUMBIA ST BKLN. Tasteful, but proud, the mark of an enterprise that seemed confident they would be around for a good long while. And they were, from 1869 to 1930. Their office address and everything near it disappeared during the creation of the Battery Tunnel Plaza in the late 1940s, now occupied by the expansive Triborough Bridge & Tunnel Authority building. And their workshops that occupied most of the block across from their office is now a parking lot for the Authority. Ah, but one hundred years ago, that block was much in the news. In fact, in every newspaper. Because it was going to be the site of the first rooftop landing strip for airplanes.

The Gibbons were one of the largest employers in Red Hook. 300 to 500 laborers and craftsmen worked for the company at any given time between its Civil War era founding and its dissolution as the Great Depression began. In addition to residential buildings in South Brooklyn, they erected a Bush Terminal warehouse, City schools, the Pioneer movie theater on Richards Street across from Coffey Park (now a medical building), most of the structures in the old Todd Shipyards, as well as many projects big and small ranging from midtown Manhattan to Far Rockaway.

The business was created by an Irish immigrant, Michael Gibbons. When he got sick in 1894 and died two years later at the age of 60, his son Richard took the reins, inheriting a half a million dollars of construction contracts to manage. Richard Gibbons was a visionary, an innovator and very generous, especially with other people’s money. Since Excel spreadsheets wouldn’t be invented for eighty years, he failed to factor in the delay between accounts receivable and payable. So to buy the supplies his company needed, he started forging checks, using the names of three elderly friends of his recently departed father, to the tune of about $150,000. He would restore their accounts immediately so his “borrowing” went undetected for years until an economic slowdown led to his ruin. Tried in Brooklyn Supreme Court and found incredibly guilty, he was sent up the Hudson to Sing Sing prison for 30 months.

There the story should have ended…except it didn’t because I need a few hundred more words to get to airplanes on Red Hook rooftops…Upon his release, Richard resumed control of the “Gibbons Company” and built the business back up again. It didn’t hurt that he was a cousin of the most powerful and famous Catholic in America, James Cardinal Gibbons of Baltimore, a fierce defender of the working man and his right to unionize. This undoubtedly helped him land jobs building rectories, many new parochial schools and even an elevator for the new Cardinal John Murphy Farley in his Madison Avenue residence across from St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Both Cardinals were supporters of the World War in 1917 and the Gibbons Company won some lucrative construction contracts from the War Department. That’s when Gibbons got interested in aviation.

The Wright Brothers pioneered motorized flight in 1903, while Gibbons did his time at Sing Sing, and less than ten years later seaplanes were being lowered and retrieved from the water via cranes on large naval ships for reconnaissance flights. But it wasn’t until 1917 that the British successfully landed a wheeled aircraft on a moving warship. Perhaps Gibbons work in the Hook’s shipyards and building electric elevators got him to thinking about such things but somehow he got the idea to build a device that would create a platform for planes to launch and land on rooftops, boats and even rocky coasts.

He imagined a steel runway mounted on a large electro-mechanical turntable that would require a clearance of 200×60 feet to operate, so he envisioned it being deployed on top of large factories and skyscrapers. But first he needed one of his company’s engineers to help him draw up the plans and get it patented. And so on August 15, 1919, the Feast of the Assumption (a Holy Day of Obligation for Catholics), less than a year after the War ended, Richard Gibbons filed an application for an “Airplane Receiving Apparatus…so as to produce sudden changes in velocity within a limited space to enable a plane to land upon a building or ship.” Gibbons went on to write that “it will be obvious that reversed movements between the apparatus and airplane would assist in starting an airplane within a limited space.”

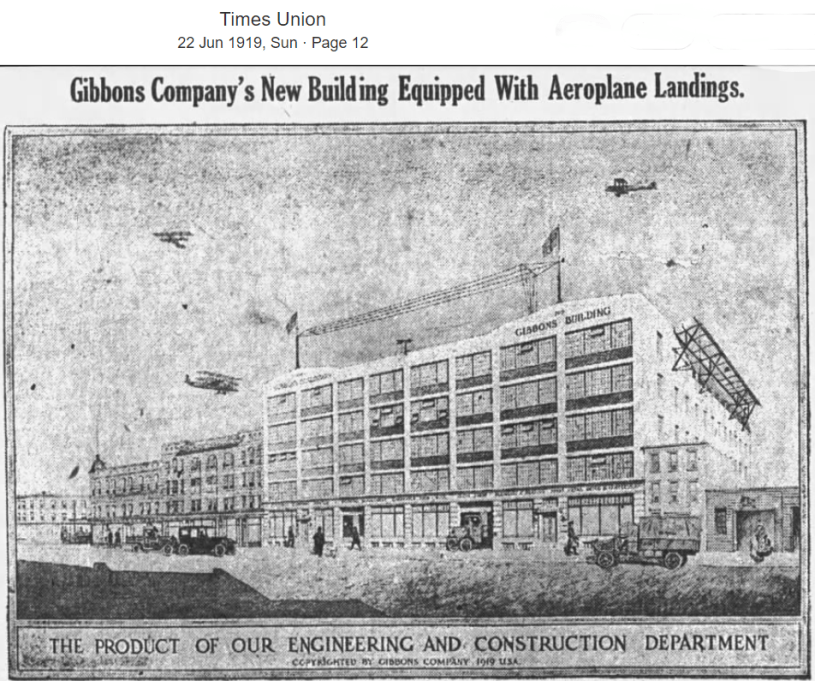

Perhaps to create buzz for his invention, Gibbons issued an elaborate press release two months before his filing. In it he boldly claimed that although he had only fabricated a model, he had just broken ground to build a five story factory measuring 175×175 feet, replacing all his shops along Columbia Street, and on that roof he would install the first Airplane Receiving (and launching) Apparatus. Included in his release was an artist’s rendering of the plan. The press ate it up. But the Department of Buildings suffered indigestion.

In 1920, his patent was granted by the U.S. Patent Office. That was the easy part. Construction of his new factory on Columbia Street, just south of Hamilton Avenue, complete with a rooftop landing strip, was a tad more difficult. In 1916 the City passed a zoning resolution, regulating all new construction for the first time. Its primary goal was to prevent buildings from reaching heights that would block out light in the immediate area. While the factory itself was of permissible height for Columbia Street, the contraption on the roof might have increased the height to an unacceptable level and the zoning laws provided no exception for rooftop airplanes. Moreover there appeared to be an issue relating to the uses planned within the building itself. Gibbons fought the determination and continued to test the device.

A hearing on the matter in 1920 before the Bureau of Standards & Appeals apparently went against him. In the meantime, Gibbons began constructing a new building at the foot of 24th Street in the Todd Shipyards and announced that eventually the structure would sport one of his landing strips. Finishing another shipyard building at the foot of Clinton Street a year later, he stated he was “perfecting the device.”

In April 1923 Gibbons wrangled a “certificate of merit” from the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce for his business having survived some 54 years and used the occasion to announce that his rooftop landing strip “would soon be placed in universal use.”

In February 1924 another press splash occurred, accompanied by a drawing of Gibbons device atop a large center-City building. Gibbons gushed to a Brooklyn Eagle reporter that his device “can be used on railroad stations, post offices, station houses, hospitals, hotels, police headquarters, fire houses, office buildings, apartment houses.” The airplane receiving apparatus was said to have been patented for use around the globe and examined by military aviation experts “with great interest.” Meanwhile, although Gibbons’ building was stalled at a height of two stories, he claimed it would be completed soon. But aside from regular ads in the paper for his company, Gibbons was not heard from again for the next three years.

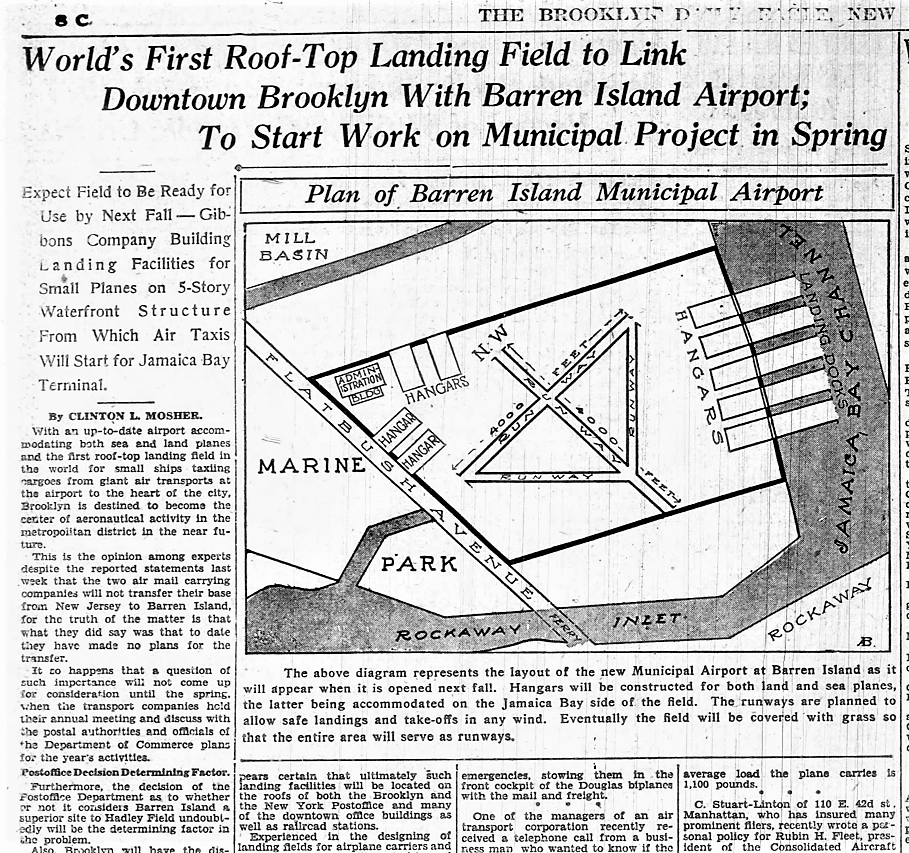

Then in May 1927 Charles Lindberg took off from Roosevelt Field in Nassau County on the first successful solo flight across the Atlantic – and the longest to date – landing 2,000 miles away in Paris. Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia, himself a flyer during the World War, was incensed that puny Garden City would be enshrined as the starting point for this momentous event and vowed to build a large municipal airport. A site at the foot of Flatbush Avenue was eventually chosen by a Federal presidential commission in February 1928, later dubbed Floyd Bennett Field.

LaGuardia was not happy. He wanted the airfield to be on Governor’s Island because its proximity to Manhattan would help him convince the US Postal Service to abandon Newark Airport as the destination terminal for all air mail drops for the NYC area. It was a matter of prestige. But Floyd Bennett was about 15 miles distant from the main Post Office on West 34th Street, a very long and slow motor trip – even then, traffic sucked – whereas the mail from Newark could be swiftly ferried across the Hudson.

Richard Gibbons to the rescue! He suddenly resurfaced in the press as soon as the Floyd Bennett location was approved by the City in February 1928. The Gibbons solution? He would take delivery of mail dispatched from Floyd Bennett on his Columbia Street roof, elevator it down to trucks below and off they would go to post offices hither and yon. Moreover, Gibbons would deploy his contraptions on as many post office roofs as necessary. Two flying aces from Germany and Ireland would be examining his device shortly at his Columbia Street workshop, he claimed, with a view toward adopting it throughout Europe per a royalty agreement.

All he needed was to get permission from the damn zoning people to finish his damn building!

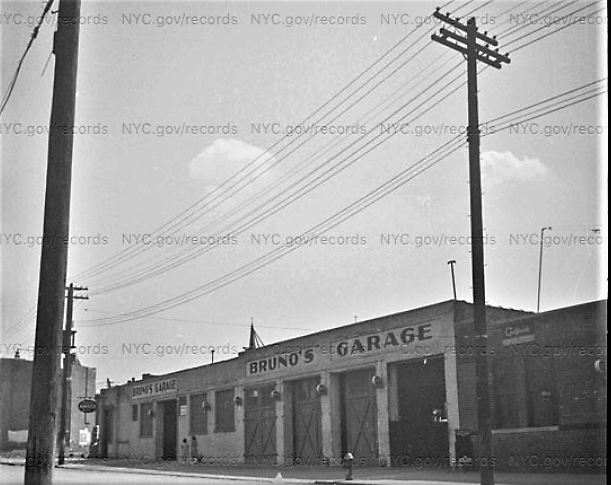

Alas and alack, it was not to be. Runways on roofs was a bridge too far for everybody but Gibbons. By the time Floyd Bennett opened to freight traffic in 1930, Gibbons had dissolved his business. He died four years later in his bed at 25 1st Place in Carroll Gardens, possibly fantasizing about splitting the atom in his basement. His workshops became an auto auction site and the two story factory became Bruno’s Garage, demolished after WWII to build the Battery Tunnel.

In 1925, T.S. Elliot famously wrote, “Between the idea and reality falls the shadow.” He might have been alluding to Richard Gibbons’ idea to install a landing strip atop a big new Columbia Street factory. The sad reality was that the City’s zoning resolution cast a very big shadow.

RED HOOK STAR-REVUE